Andrology Department Introduction

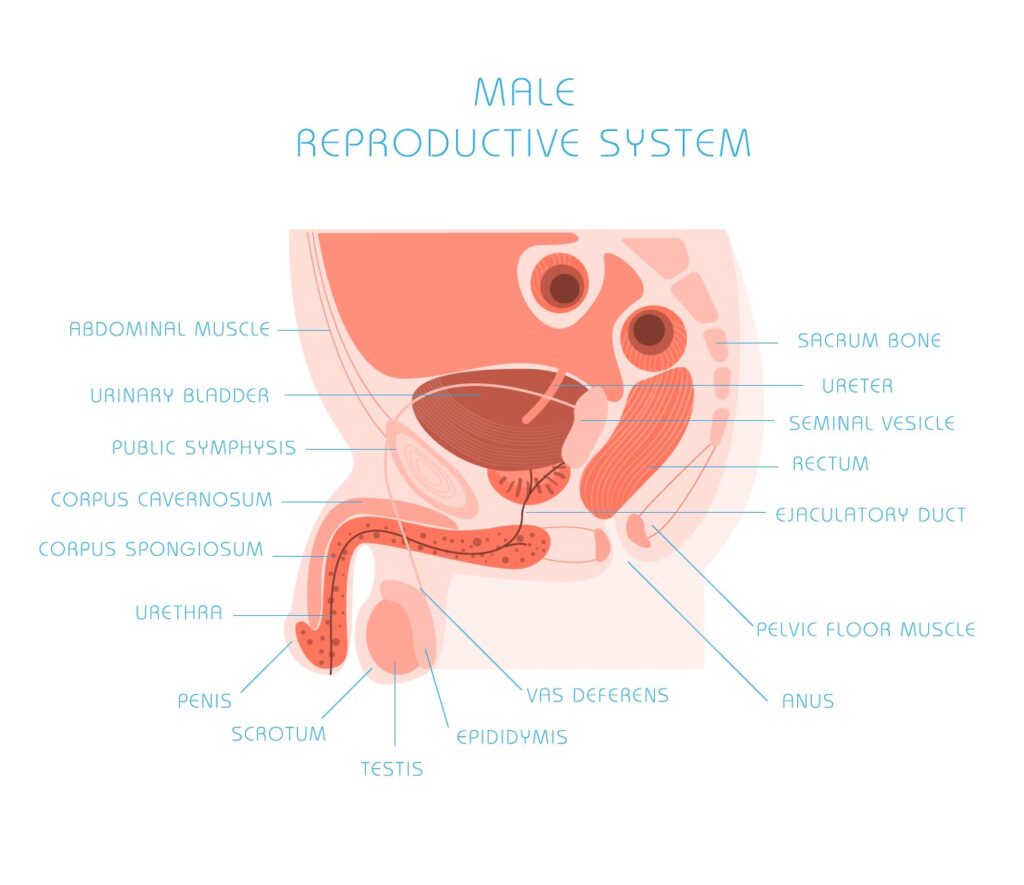

Andrology is a name for the medical specialty that deals with male health, particularly relating to the problems of the male reproductive system and urological problems that are unique to men. It is the counterpart to gynaecology, which deals with medical issues which are specific to female health, especially reproductive and urologic health.

Process

Andrology covers anomalies in the connective tissues pertaining to the genitalia, as well as changes in the volume of cells, such as in genital hypertrophy or macrogenitosomia.

From reproductive and urologic viewpoints, male-specific medical and surgical procedures include vasectomy, vasovasostomy (one of the vasectomy reversal procedures), orchidopexy, circumcision, sperm/semen cryopreservation, surgical sperm retrieval, semen analysis (for fertility or post-vasectomy), sperm preparation for assisted reproductive technology (ART) as well as intervention to deal with male genitourinary disorders such as the following:

What is Andrology?

Andrologists are medical specialists who diagnose, treat, and manage various conditions related to male reproductive health. They work closely with patients to assess their symptoms, perform diagnostic tests, and recommend appropriate treatment options. Here are some common aspects of an andrologist’s work and the treatments they provide:

1. Infertility Treatment: Andrologists play a key role in evaluating and managing male infertility. They assess factors such as sperm quality, quantity, and motility through semen analysis. Based on the results, they may recommend lifestyle modifications, such as changes in diet or reducing exposure to certain environmental factors. Additionally, they may suggest medications, hormone therapy, or surgical interventions to address specific causes of infertility, such as varicoceles or obstructions in the reproductive tract. Andrologists may also collaborate with reproductive specialists to perform assisted reproductive techniques like in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Large numbers of people are affected by infertility in their lifetime, according to a new report published today by WHO. Around 17.5% of the adult population – roughly 1 in 6 worldwide – experience infertility, showing the urgent need to increase access to affordable, high-quality fertility care for those in need.

The new estimates show limited variation in the prevalence of infertility between regions. The rates are comparable for high-, middle- and low-income countries, indicating that this is a major health challenge globally. Lifetime prevalence was 17.8% in high-income countries and 16.5% in low- and middle-income countries.

“The report reveals an important truth: infertility does not discriminate,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General at WHO. “The sheer proportion of people affected show the need to widen access to fertility care and ensure this issue is no longer sidelined in health research and policy, so that safe, effective, and affordable ways to attain parenthood are available for those who seek it.”

Infertility is a disease of the male or female reproductive system, defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. It can cause significant distress, stigma, and financial hardship, affecting people’s mental and psychosocial well-being.

Despite the magnitude of the issue, solutions for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infertility – including assisted reproductive technology such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) – remain underfunded and inaccessible to many due to high costs, social stigma and limited availability.

At present, in most countries, fertility treatments are largely funded out of pocket – often resulting in devastating financial costs. People in the poorest countries spend a greater proportion of their income on fertility care compared to people in wealthier countries. High costs frequently prevent people from accessing infertility treatments or alternatively, can catapult them into poverty as a consequence of seeking care.

“Millions of people face catastrophic healthcare costs after seeking treatment for infertility, making this a major equity issue and all too often, a medical poverty trap for those affected,” said Dr Pascale Allotey, Director of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research at WHO, including the United Nations’ Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP). “Better policies and public financing can significantly improve access to treatment and protect poorer households from falling into poverty as a result.”

While the new report shows convincing evidence of the high global prevalence of infertility, it highlights a persistent lack of data in many countries and some regions. It calls for greater availability of national data on infertility disaggregated by age and by cause to help with quantifying infertility, as well as knowing who needs fertility care and how risks can be reduced.

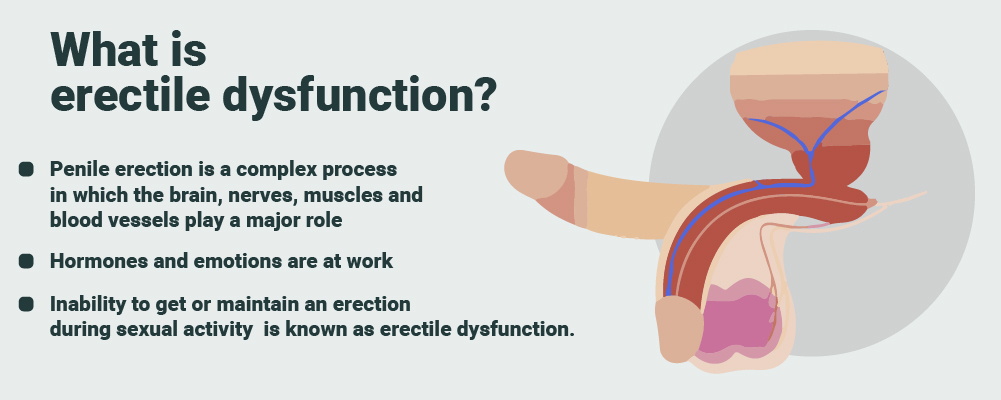

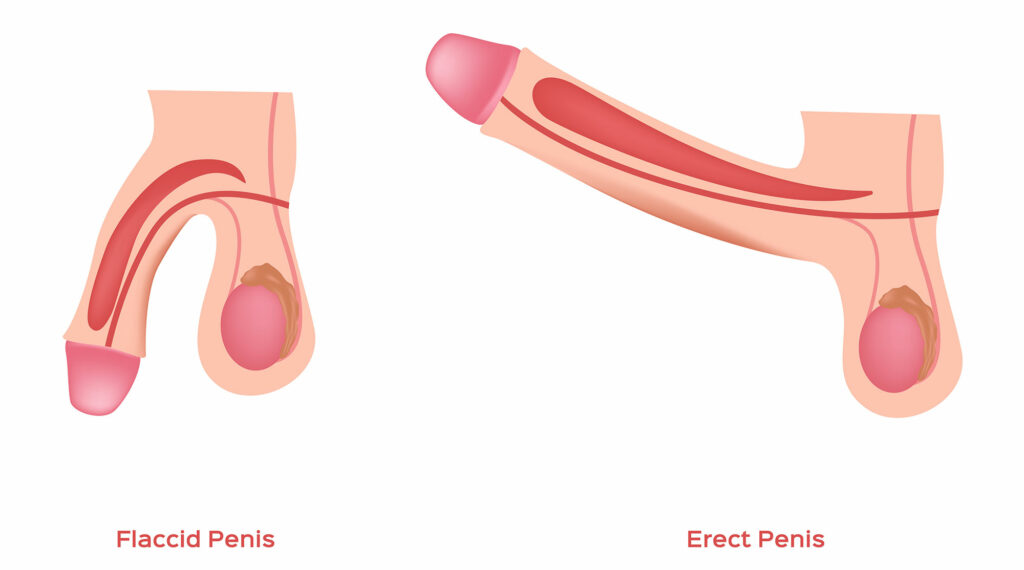

2. Erectile Dysfunction (ED) Treatment: Andrologists evaluate and treat erectile dysfunction, which involves the inability to achieve or maintain an erection. They assess potential underlying causes, which may be physical or psychological. Treatment options may include medications like phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, such as sildenafil (Viagra) or tadalafil (Cialis). They may also suggest lifestyle changes, such as regular exercise, a healthy diet, and stress reduction techniques. In some cases, psychological counseling or therapy may be recommended to address any emotional or psychological factors contributing to ED.

What causes erectile dysfunction?

Many different factors affecting your vascular system , nervous system , and endocrine system can cause or contribute to ED.

Although you are more likely to develop ED as you age, aging does not cause ED. ED can be treated at any age.

Certain diseases and conditions

The following diseases and conditions can lead to ED:

- type 2 diabetes

- heart and blood vessel disease

- atherosclerosis

- high blood pressure

- chronic kidney disease

- multiple sclerosis

- Peyronie’s disease

- injury from treatments for prostate cancer

- injury to the penis, spinal cord, prostate, bladder, or pelvis

- surgery for bladder cancer

Men who have diabetes are two to three times more likely to develop ED than men who do not have diabetes. Read more about diabetes and sexual and urologic problems.

Taking certain medicines

ED can be a side effect of many common medicines, such as

- blood pressure medicines

- antiandrogens—medicines used for prostate cancer therapy

- antidepressants

- tranquilizers, or prescription sedatives—medicines that make you calmer or sleepy

- appetite suppressants, or medicines that make you less hungry

- ulcer medicines

View a list of specific medicines that may cause ED

Certain psychological or emotional issues

Psychological or emotional factors may make ED worse. You may develop ED if you have one or more of the following:

- fear of sexual failure

- anxiety

- depression

- guilt about sexual performance or certain sexual activities

- low self-esteem

- stress—about sexual performance, or stress in your life in general

Certain health-related factors and behaviors

The following health-related factors and behaviors may contribute to ED:

- smoking

- drinking too much alcohol

- using illegal drugs

- being overweight

- not being physically active

3. Hormone Replacement Therapy: Andrologists manage hormonal disorders in men, particularly hypogonadism, which is characterized by low testosterone levels. They evaluate hormone levels through blood tests and assess symptoms like fatigue, decreased libido, and muscle weakness. If necessary, they may prescribe hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to restore testosterone levels to normal ranges. HRT can be administered through various methods, including injections, gels, patches, or implants.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is a treatment to relieve symptoms of the menopause. It replaces hormones that are at a lower level as you approach the menopause.

Benefits of HRT

The main benefit of HRT is that it can help relieve most of the menopausal symptoms, such as:

- hot flushes

- night sweats

- mood swings

- vaginal dryness

- reduced sex drive

Many of these symptoms pass after a few years, but they can be unpleasant and taking HRT can offer relief for many women.

It can also help prevent weakening of the bones (osteoporosis), which is more common after the menopause.

Risks of HRT

Some types of HRT can increase your risk of breast cancer.

The benefits of HRT are generally believed to outweigh the risks. But speak to a GP if you have any concerns about taking HRT.

Read more about the risks of HRT.

How to get started on HRT

Speak to a GP if you’re interested in starting HRT.

You can usually begin HRT as soon as you start experiencing menopausal symptoms and will not usually need to have any tests first.

A GP can explain the different types of HRT available and help you choose one that’s suitable for you.

You’ll usually start with a low dose, which may be increased at a later stage. It may take a few weeks to feel the effects of treatment and there may be some side effects at first.

A GP will usually recommend trying treatment for 3 months to see if it helps. If it does not, they may suggest changing your dose, or changing the type of HRT you’re taking.

Who can take HRT

Most women can have HRT if they’re having symptoms associated with the menopause.

But HRT may not be suitable if you:

- have a history of breast cancer, ovarian cancer or womb cancer

- have a history of blood clots

- have untreated high blood pressure – your blood pressure will need to be controlled before you can start HRT

- have liver disease

- are pregnant – it’s still possible to get pregnant while taking HRT, so you should use contraception until 2 years after your last period if you’re under 50, or for 1 year after the age of 50

In these circumstances, alternatives to HRT may be recommended instead.

Types of HRT

There are many different types of HRT and finding the right 1 for you can be difficult.

There are different:

- HRT hormones – most women take a combination of the hormones oestrogen and progestogen, although women who do not have a womb can take oestrogen on its own

- ways of taking HRT – including tablets, skin patches, gels and vaginal creams, pessaries or rings

- HRT treatment plans – HRT medicine may be taken without stopping, or used in cycles where you take oestrogen without stopping but only take progestogen every few weeks

A GP can give you advice to help you choose which type is best for you. You may need to try more than 1 type before you find 1 that works best.

Find out more about the different types of HRT.

Stopping HRT

There’s no limit on how long you can take HRT, but talk to a GP about how long they recommend you take the treatment.

Most women stop taking it once their menopausal symptoms pass, which is usually after a few years.

Women who take HRT for more than 1 year have a higher risk of breast cancer than women who never use HRT. The risk is linked to all types of HRT except vaginal oestrogen.

The increased risk of breast cancer falls after you stop taking HRT, but some increased risk remains for more than 10 years compared to women who have never used HRT.

When you decide to stop, you can choose to do so suddenly or gradually.

Gradually decreasing your HRT dose is usually recommended because it’s less likely to cause your symptoms to come back in the short term.

Contact a GP if you have symptoms that persist for several months after you stop HRT, or if you have particularly severe symptoms. You may need to start HRT again.

Side effects of HRT

As with any medicine, HRT can cause side effects. But these will usually pass within 3 months of starting treatment.

Common side effects include:

- breast tenderness

- headaches

- feeling sick

- indigestion

- abdominal (tummy) pain

- vaginal bleeding

Alternatives to HRT

If you’re unable to take HRT or decide not to, you may want to consider alternative ways of controlling your menopausal symptoms.

Alternatives to HRT include:

- lifestyle measures. such as exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, cutting down on coffee, alcohol and spicy foods, and stopping smoking

- tibolone – a medicine that’s similar to combined HRT (oestrogen and progestogen), but may not be as effective and is only suitable for women who had their last period more than 1 year ago

- antidepressants – some antidepressants can help with hot flushes and night sweats, although they can also cause unpleasant side effects such as agitation and dizziness

- clonidine – a non-hormonal medicine that may help reduce hot flushes and night sweats in some women, although any benefits are likely to be small

Several remedies (such as bioidentical hormones) are claimed to help with menopausal symptoms, but these are not recommended because it’s not clear how safe and effective they are.

Bioidentical hormones are not the same as body identical hormones. Body identical hormones, or micronised progesterone, can be prescribed to treat menopausal symptoms.

4. Sexual Health Treatment: Andrologists address a range of sexual health concerns in men, such as premature ejaculation, delayed ejaculation, or loss of libido. They provide counseling and behavioral interventions to address psychological factors affecting sexual function. In some cases, medications or topical creams may be prescribed to manage specific issues.

Key facts

- More than 1 million sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are acquired every day worldwide, the majority of which are asymptomatic.

- Each year there are an estimated 374 million new infections with 1 of 4 curable STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomoniasis.

- More than 500 million people 15–49 years are estimated to have a genital infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV or herpes) (1).

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is associated with over 311 000 cervical cancer deaths each year (2).

- Almost 1 million pregnant women were estimated to be infected with syphilis in 2016, resulting in over 350 000 adverse birth outcomes (3).

- STIs have a direct impact on sexual and reproductive health through stigmatization, infertility, cancers and pregnancy complications and can increase the risk of HIV.

- Drug resistance is a major threat to reducing the burden of STIs worldwide.

Overview

More than 30 different bacteria, viruses and parasites are known to be transmitted through sexual contact, including vaginal, anal and oral sex. Some STIs can also be transmitted from mother-to-child during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. Eight pathogens are linked to the greatest incidence of STIs. Of these, 4 are currently curable: syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis. The other 4 are incurable viral infections: hepatitis B, herpes simplex virus (HSV), HIV and human papillomavirus (HPV).

In addition, emerging outbreaks of new infections that can be acquired by sexual contact such as monkeypox, Shigella sonnei, Neisseria meningitidis, Ebola and Zika, as well as re-emergence of neglected STIs such as lymphogranuloma venereum. These herald increasing challenges in the provision of adequate services for STIs prevention and control.

Scope of the problem

STIs have a profound impact on sexual and reproductive health worldwide.

More than 1 million STIs are acquired every day. In 2020, WHO estimated 374 million new infections with 1 of 4 STIs: chlamydia (129 million), gonorrhoea (82 million), syphilis (7.1 million) and trichomoniasis (156 million). More than 490 million people were estimated to be living with genital herpes in 2016, and an estimated 300 million women have an HPV infection, the primary cause of cervical cancer and anal cancer among men who have sex with men. An estimated 296 million people are living with chronic hepatitis B globally.

STIs can have serious consequences beyond the immediate impact of the infection itself.

- STIs like herpes, gonorrhoea and syphilis can increase the risk of HIV acquisition.

- Mother-to-child transmission of STIs can result in stillbirth, neonatal death, low-birth weight and prematurity, sepsis, neonatal conjunctivitis and congenital deformities.

- HPV infection causes cervical and other cancers.

- Hepatitis B resulted in an estimated 820 000 deaths in 2019, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. STIs such as gonorrhoea and chlamydia are major causes of pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility in women.

Prevention of STIs

When used correctly and consistently, condoms offer one of the most effective methods of protection against STIs, including HIV. Although highly effective, condoms do not offer protection for STIs that cause extra-genital ulcers (i.e., syphilis or genital herpes). When possible, condoms should be used in all vaginal and anal sex.

Safe and highly effective vaccines are available for 2 viral STIs: hepatitis B and HPV. These vaccines have represented major advances in STI prevention. By the end of 2020, the HPV vaccine had been introduced as part of routine immunization programmes in 111 countries, primarily high- and middle-income countries. To eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem globally, high coverage targets for HPV vaccination, screening and treatment of precancerous lesions, and management of cancer must be reached by 2030 and maintained at this high level for decades.

Research to develop vaccines against genital herpes and HIV is advanced, with several vaccine candidates in early clinical development. There is mounting evidence suggesting that the vaccine to prevent meningitis (MenB) provides some cross-protection against gonorrhoea. More research into vaccines for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomoniasis are needed.Other biomedical interventions to prevent some STIs include adult voluntary medical male circumcision, microbicides, and partner treatment. There are ongoing trials to evaluate the benefit of pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis of STIs and their potential safety weighed with antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Diagnosis of STIs

STIs are often asymptomatic. When symptoms occur, they can be non-specific. Moreover, laboratory tests rely on blood, urine or anatomical samples. Three anatomical sites can carry at least one STI. These differences are modulated by sex and sexual risk. These differences can mean the diagnosis of STIs is often missed and individuals are frequently treated for 2 or more STIs.

Accurate diagnostic tests for STIs (using molecular technology) are widely used in high-income countries. These are especially useful for the diagnosis of asymptomatic infections. However, they are largely unavailable in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Even in countries where testing is available, it is often expensive and not widely accessible. In addition, the time it takes for results to be received is often long. As a result, follow-up can be impeded and care or treatment can be incomplete.

On the other hand, inexpensive, rapid tests are available for syphilis, hepatitis B and HIV. The rapid syphilis test and rapid dual HIV/syphilis tests are used in several resource-limited settings.

Several other rapid tests are under development and have the potential to improve STI diagnosis and treatment, especially in resource-limited settings.

Treatment of STIs

Effective treatment is currently available for several STIs.

- Three bacterial (chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis) and one parasitic STIs (trichomoniasis) are generally curable with existing single-dose regimens of antibiotics.

- For herpes and HIV, the most effective medications available are antivirals that can modulate the course of the disease, though they cannot cure the disease.

- For hepatitis B, antivirals can help fighting the virus and slowing damage to the liver.

AMR of STIs – in particular gonorrhoea – has increased rapidly in recent years and has reduced treatment options. The Gonococcal AMR Surveillance Programme (GASP) has shown high rates of resistance to many antibiotics including quinolone, azithromycin and extended-spectrum cephalosporins, a last-line treatment (4).

AMR for other STIs like Mycoplasma genitalium, though less common, also exists.

STI case management

LMICs rely on identifying consistent, easily recognizable signs and symptoms to guide treatment, without the use of laboratory tests. This approach – syndromic management – often relies on clinical algorithms and allows health workers to diagnose a specific infection based on observed syndromes (e.g., vaginal/urethral discharge, anogenital ulcers, etc). Syndromic management is simple, assures rapid, same-day treatment, and avoids expensive or unavailable diagnostic tests for patients with symptoms. However, this approach results in overtreatment and missed treatment as the majority of STIs are asymptomatic. Thus, WHO recommends countries to enhance syndromic management by gradually incorporating laboratory testing to support diagnosis. In settings where quality assured molecular assays are available, it is recommended to treat STIs based on laboratory tests. Moreover, STI screening strategies are essential for those at higher risk of infection, such sex workers, men who have sex with men, adolescents in some settings and pregnant women.

To interrupt transmission and prevent re-infection, treating sexual partners is an important component of STI case management.

Controlling the spread

Behaviour change is complex

Despite considerable efforts to identify simple interventions that can reduce risky sexual behaviour, behaviour change remains a complex challenge.

Information, education and counselling can improve people’s ability to recognize the symptoms of STIs and increase the likelihood that they will seek care and encourage a sexual partner to do so. Unfortunately, lack of public awareness, lack of training among health workers, and long-standing, widespread stigma around STIs remain barriers to greater and more effective use of these interventions.

Health services for screening and treatment of STIs remain weak

People seeking screening and treatment for STIs face numerous problems. These include limited resources, stigmatization, poor quality of services and often out-of-pocket expenses.

Some populations with the highest rates of STIs – such as sex workers, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, prison inmates, mobile populations and adolescents in high burden countries for HIV – often do not have access to adequate and friendly health services.

In many settings, STI services are often neglected and underfunded. These problems lead to difficulties in providing testing for asymptomatic infections, insufficient number of trained personnel, limited laboratory capacity and inadequate supplies of appropriate medicines.

WHO response

Our work is currently guided by the Global health sector strategy on HIV, Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2022–2030. Within this framework, WHO:

- develops global targets, norms and standards for STI prevention, testing and treatment;

- supports the estimation and economic burden of STIs and the strengthening of STI surveillance;

- globally monitors AMR to gonorrhoea; and

- leads the setting of the global research agenda on STIs, including the development of diagnostic tests, vaccines and additional drugs for gonorrhoea and syphilis.

As part of its mission, WHO supports countries to:

- develop national strategic plans and guidelines;

- create an encouraging environment allowing individuals to discuss STIs, adopt safer sexual practices, and seek treatment;

- scale-up primary prevention (condom availability and use, etc.);

- increase integration of STI services within primary healthcare services;

- increase accessibility of people-centred quality STI care;

- facilitate adoption of point-of-care tests;

- enhance and scale-up health intervention for impact, such as hepatitis B and HPV vaccination, syphilis screening in priority populations;

- strengthen capacity to monitoring STIs trends; and

- monitor and respond to AMR in gonorrhoea.

5. Surgical Interventions: Andrologists may perform surgical procedures to address conditions affecting the male reproductive system. For example, they may treat conditions like varicoceles (enlarged veins in the scrotum) or perform vasectomy procedures for contraception purposes. They may also collaborate with urologists for surgical interventions related to conditions such as testicular or prostate disorders.

It’s important to note that the specific treatments provided by an andrologist can vary depending on the individual patient and their unique circumstances. Andrologists work closely with other healthcare professionals, such as urologists, endocrinologists, and reproductive specialists, to ensure comprehensive and personalized care for their patients.

Reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI) is a vast and evolving field, where multiple ever-expanding fields of knowledge converge. The modern practice of reproductive endocrinology and infertility is now completely dependent on the combined expertise of clinical embryologists, geneticists, andrologists, and reproductive surgeons. That is because the proficiency expected in any one of these fields has reached levels that are impossible for a single provider to achieve and maintain. If most reproductive endocrinologists cannot be reproductive surgeons, then it goes without saying that the definition of a reproductive surgeon must evolve. Is the reproductive surgeon still a reproductive endocrinologist who focuses on the surgical aspects of this field? Or rather a general gynecologist with special training in laparoscopy, to whom REI subspecialists can outsource the minimally invasive microsurgery that they can no longer perform? This is not a matter of semantics. Definitions, standardization, and certifications are an essential feature of patient-centered care in developed countries. We should recognize however that cultural differences do exist between developed countries on this point. Reproductive endocrinology pioneers in the U.S. have fought particularly hard to establish a high bar for special certification. Indeed, our subspecialty was one of the first medical subspecialties to be established in the U.S., in 1972 (1). Similar pathways to certification have emerged more recently within the Royal Colleges of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, while the achievements of the European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in this field remain limited, and elsewhere in the world a separate REI subspecialty is virtually nonexistent. Hence, while most of the world’s medical systems do not offer formal training and certification for REI, we are approaching fifty years of continuous development of this subspecialty in the U.S. As we continue to mature, one of the identity challenges that we face is how much of a surgical subspecialty we want to be.